A castle

was primarily a military structure, occupied by its masters on

their continual perambulation of their  territories. When the lord was not in residence the

castle was looked after by a constable and one or two paid

soldiers. In time of war the garrison would rapidly be augmented

by the local populace and landholders who owed military service

to their lord for the privilege of holding their lands. This may

seem haphazard today, but at that time it was impossible to move

a large attacking force quickly, therefore a castle garrison had

time to form the defence. Generally the feudal military land

obligation was a period of service at the tenant's own cost,

sometimes in person, sometimes by a certain number of knights,

mounted infantry, bowmen or footmen for a set number of days.

Initially the service was for 40 days and the knights were

accommodated in their own houses in the castle, but as these

fees, as they were called, were split amongst co-heirs the amount

of service would diminish and by the thirteenth century many

obligations were down to just a few days. For a lord wishing to

undertake military operations such a piecemeal and part-time army

was obviously less than satisfactory, and so as time went by

military obligations tended to be relinquished and replaced by a

cash payment, generally known as scutage or shield money. This

enabled a lord to hire professional armed forces who would fight

whilst pay was forthcoming and not go home at times of vital need

simply because the length of service they owed to their lord was

expended.

territories. When the lord was not in residence the

castle was looked after by a constable and one or two paid

soldiers. In time of war the garrison would rapidly be augmented

by the local populace and landholders who owed military service

to their lord for the privilege of holding their lands. This may

seem haphazard today, but at that time it was impossible to move

a large attacking force quickly, therefore a castle garrison had

time to form the defence. Generally the feudal military land

obligation was a period of service at the tenant's own cost,

sometimes in person, sometimes by a certain number of knights,

mounted infantry, bowmen or footmen for a set number of days.

Initially the service was for 40 days and the knights were

accommodated in their own houses in the castle, but as these

fees, as they were called, were split amongst co-heirs the amount

of service would diminish and by the thirteenth century many

obligations were down to just a few days. For a lord wishing to

undertake military operations such a piecemeal and part-time army

was obviously less than satisfactory, and so as time went by

military obligations tended to be relinquished and replaced by a

cash payment, generally known as scutage or shield money. This

enabled a lord to hire professional armed forces who would fight

whilst pay was forthcoming and not go home at times of vital need

simply because the length of service they owed to their lord was

expended.

When it came to

castles proper, the defensive quality of the building was

paramount to a lord, his splendour in residence came second. In the early

Medieval period, castles in the true sense of the word, were for

defence. Other buildings more like country houses were built

where the primary function was living accommodation. Not

surprisingly these lightly fortified houses were built away from

the dangerous frontiers. Obviously such distinction between

fortresses and fortified houses still existed though now it is

often difficult to tell what was the difference then.

When it came to

castles proper, the defensive quality of the building was

paramount to a lord, his splendour in residence came second. In the early

Medieval period, castles in the true sense of the word, were for

defence. Other buildings more like country houses were built

where the primary function was living accommodation. Not

surprisingly these lightly fortified houses were built away from

the dangerous frontiers. Obviously such distinction between

fortresses and fortified houses still existed though now it is

often difficult to tell what was the difference then.

Castles are often found at the end of ridges, on hill tops, at the junction of rivers or in marshy ground, all of which offered immediate advantages to the defender. Once the position had been chosen, elements were added to make the defensive attributes of the site greater. A large ditch might be dug and powerful ramparts built with the resultant spoil. Often a huge mound of earth called a motte would be made to dominate the area. Timber works might be built on or in these earthen defences, sometimes a palisade round the edge of the ditch and on top of the rampart. Then a wooden tower might be built on or, in several cases, within the motte.

After

the accession of Henry II castle warfare began slowly to take on

a different character. On the one  hand, defence was assisted by developments in the

plan and construction of castles; on the other, the weaponry of

attack was generally improved. In the castle itself walls became

thicker; corner and mural towers were built to give enfilading

fire. Loops were located in the walls with increasing regard both

to the field of fire which they could control and to the

convenience of the archer. The walls were crowned with

battlements which gave protection to the defenders, and the gaps

between the merlons were often guarded by hinged flaps. The

entrance, always the most vulnerable point in the circuit of

walls, was protected by a gatehouse, which, when fully developed,

consisted usually of an entrance tunnel set back between

drum-towers and further protected by drawbridge, portcullis and

stout oaken gates.

hand, defence was assisted by developments in the

plan and construction of castles; on the other, the weaponry of

attack was generally improved. In the castle itself walls became

thicker; corner and mural towers were built to give enfilading

fire. Loops were located in the walls with increasing regard both

to the field of fire which they could control and to the

convenience of the archer. The walls were crowned with

battlements which gave protection to the defenders, and the gaps

between the merlons were often guarded by hinged flaps. The

entrance, always the most vulnerable point in the circuit of

walls, was protected by a gatehouse, which, when fully developed,

consisted usually of an entrance tunnel set back between

drum-towers and further protected by drawbridge, portcullis and

stout oaken gates.

The defence was assisted from the later years of the 12th century by the introduction of the crossbow. The traditional English bow was the short-bow, with a range of no more than 200 metres. The medieval crossbow derived from the classic balista. It was a more accurate weapon, with a longer range, and the quarrel which it fired was in all respects more deadly than a simple arrow. The crossbow gave the defence a considerable advantage during the 13th century. But it's rate of fire was slow and the archer needed protection while drawing his bow. Loops facilitated sighting the bow, and the wide internal splay gave the bowman room to handle his weapon. The crossbow was a remarkably accurate weapon, capable of picking off defenders on the walls and even of shooting a quarrel through a loop and hitting the defender. Its accuracy and range led to the construction of wooden shutters and bretaches over the tops of castle walls.

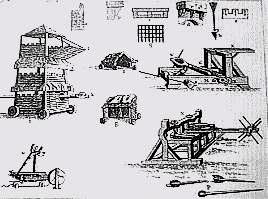

Attack was assisted by a variety of "engines" which threw missiles, usually stones, into the castle. They made use of tension, as in a bow, of torsion and of counterpoise. Most had been used in classical times. All were used in the Middle Ages to beat down walls and crush buildings and also defended against all that approached their walls too closely. The term ballista usually denoted a great crossbow operated by the tension of the bow; the springal relied on the tension of a bent beam of wood, and the mangonel on the torsion of tightly twisted rope. Only one engine was the invention of the Middle Ages, the trebuchet. It relied on a counterpoise and was simpler in design and construction than most others. It was usual to drag these machines around the country as need arose.

Attackers had a range of

options. They could pulverize both the external walls and

buildings within by their artillery; they could pick away at the

walls with a "bore," or undermine them by tunnelling,

and they could make a direct assault either with ladders or by

building a mobile wooden tower which could be advanced to the

walls. In the last resort a castle could be isolated and forced

into surrender by starvation. All methods were used. Most siege

engines were capable of throwing a stone of 300 lbs or more a

distance of at least 150 metres. Wooden towers were sometimes

pushed close to the walls, which were then assaulted by foot

soldiers gathered on their upper levels.

Attackers had a range of

options. They could pulverize both the external walls and

buildings within by their artillery; they could pick away at the

walls with a "bore," or undermine them by tunnelling,

and they could make a direct assault either with ladders or by

building a mobile wooden tower which could be advanced to the

walls. In the last resort a castle could be isolated and forced

into surrender by starvation. All methods were used. Most siege

engines were capable of throwing a stone of 300 lbs or more a

distance of at least 150 metres. Wooden towers were sometimes

pushed close to the walls, which were then assaulted by foot

soldiers gathered on their upper levels.

Not surprisingly,

the long, slow siege was preferred, and for this reason castles

that were at risk were usually well stocked with food. Most

provisions, however, had only a short shelf-life and had to be

frequently renewed. For the most part the attackers put their

trust in having sufficient time for the slow process of

starvation to compel the surrender of the castle. The besieged,

however, always counted on the timely arrival of a relieving

force. A set of rules was worked out and was normally adhered to.

A siege became a kind of poker game governed by strict rules. In

the siege of Dolforwyn, the garrison "gave eight hostages,

the best after the constable, as a guarantee that they will

surrender the castle on the Thursday after the close of Easter

unless they are relieved by Llywelyn, and if relieved, the

hostages are to be returned to them." The choice of date by

which the castle should be relieved or surrendered was crucial

and represented the gamble in the negotiation. Whenever a castle

was yielded the garrison was usually allowed to march away.

Not surprisingly,

the long, slow siege was preferred, and for this reason castles

that were at risk were usually well stocked with food. Most

provisions, however, had only a short shelf-life and had to be

frequently renewed. For the most part the attackers put their

trust in having sufficient time for the slow process of

starvation to compel the surrender of the castle. The besieged,

however, always counted on the timely arrival of a relieving

force. A set of rules was worked out and was normally adhered to.

A siege became a kind of poker game governed by strict rules. In

the siege of Dolforwyn, the garrison "gave eight hostages,

the best after the constable, as a guarantee that they will

surrender the castle on the Thursday after the close of Easter

unless they are relieved by Llywelyn, and if relieved, the

hostages are to be returned to them." The choice of date by

which the castle should be relieved or surrendered was crucial

and represented the gamble in the negotiation. Whenever a castle

was yielded the garrison was usually allowed to march away.

The

Castle Moil was once known as Dunakin, and dates back to the

tenth century. It served as a lookout post and fortress. Legend tells that it was built

by a daughter of a Norwegian King (Saucy Mary), who married a

MacKinnon chief, and stretched a chain across the Kyle in order

to levy a toll on ships passing through. Around the 17th century,

the castle was abandoned when the MacKinnons moved to Kilmarie.

post and fortress. Legend tells that it was built

by a daughter of a Norwegian King (Saucy Mary), who married a

MacKinnon chief, and stretched a chain across the Kyle in order

to levy a toll on ships passing through. Around the 17th century,

the castle was abandoned when the MacKinnons moved to Kilmarie.