Accomodations and Domestic Buildings

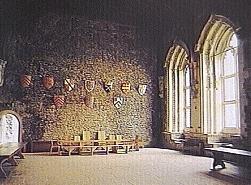

![]() hether on the motte, in the bailey, inside

the walls of the shell keep, or as a separate building within the

great curtain walls of the 13th century, the living quarters of a

castle invariably had one basic element: the hall. A large

one-room structure with a loft ceiling, the hall was sometimes on

the ground floor, but often, as is Fitz Osbern's great tower at

Chepstow, it was raised to the second story for greater security.

Early halls were aisled like a church, with rows of wooden posts

or stone pillars supporting the timber roof. Windows were

equipped with wooden shutters secured by an iron bar, but in the

11th and 12th centuries were rarely glazed. By the 13th century a

king or great baron might have "white (greenish) glass"

in some of his windows, and by the 14th century glazed windows

were common.

hether on the motte, in the bailey, inside

the walls of the shell keep, or as a separate building within the

great curtain walls of the 13th century, the living quarters of a

castle invariably had one basic element: the hall. A large

one-room structure with a loft ceiling, the hall was sometimes on

the ground floor, but often, as is Fitz Osbern's great tower at

Chepstow, it was raised to the second story for greater security.

Early halls were aisled like a church, with rows of wooden posts

or stone pillars supporting the timber roof. Windows were

equipped with wooden shutters secured by an iron bar, but in the

11th and 12th centuries were rarely glazed. By the 13th century a

king or great baron might have "white (greenish) glass"

in some of his windows, and by the 14th century glazed windows

were common.

In a ground-floor hall the floor was beaten earth,

stone or plaster; when the hall was elevated to the upper story

the floor was nearly always timber, supported either by a row of

wooden pillars in the basement below, as in Chepstow's Great

Hall, or by stone vaulting. Carpets, although used on walls,

tables, and benches, were not used as floor coverings in Britain

and northwest Europe until the 14th century. Floors were strewn

with rushes and in the later Middle Ages sometimes with herbs.

The rushes were replaced at intervals and the floor swept, but

Erasmus, noting a condition that must have been true in earlier

times, observed that often under them lay "an ancient

collection of beer, grease, fragments, bones, spittle, excrement

of dogsand cats and everything that is nasty."

In a ground-floor hall the floor was beaten earth,

stone or plaster; when the hall was elevated to the upper story

the floor was nearly always timber, supported either by a row of

wooden pillars in the basement below, as in Chepstow's Great

Hall, or by stone vaulting. Carpets, although used on walls,

tables, and benches, were not used as floor coverings in Britain

and northwest Europe until the 14th century. Floors were strewn

with rushes and in the later Middle Ages sometimes with herbs.

The rushes were replaced at intervals and the floor swept, but

Erasmus, noting a condition that must have been true in earlier

times, observed that often under them lay "an ancient

collection of beer, grease, fragments, bones, spittle, excrement

of dogsand cats and everything that is nasty."

Entrance to the hall was usually in a side wall near the lower end. When the hall was on an upper story, this entrance was commonly reached by an outside staircase next to the wall of the keep. The castle family sat on a raised dais of stone or wood at the upper end of the hall, opposite to the entrance, away from drafts and intrusion. The lord (and perhaps the lady) occupied a massive chair, sometimes with a canopy by way of emphasizing status. Everyone else sat on benches. Most dining tables were set on temporary trestles that were dismantled between meals; a permanent, or "dormant," table was another sign of prestige, limited to the greatest lords. But all tables were covered with white cloths, clean and ample. Lighting was by rushlights or candles, of wax or tallow (melted animal fat), impaled on vertical spikes or an iron candlestick with a tripod base, or held in a loop, or supported on wall brackets or iron candelabra. Oil lamps in bowl form on a stand, or suspended in a ring, provided better illumination, and flares sometimes hung from iron rings in the wall.

If the later Middle Ages had made only slight

improvements in lighting over earlier centuries, a major

technical advance had come in heating: the fireplace, an

invention of deceptive simplicity. The fireplace provided heat

both directly and by radiation from the stones at the back, from

the hearth, and finally, from the opposite wall, which was given

extra thickness to absorb the heat and warm the room after the

fire had burned low. The ancestor of the fireplace was the

central open hearth, used in ground-level halls in Saxon times

and often into later centuries. Such a hearth may have heated one

of the two halls of Chepstow's 13th-century domestic range, where

there are no traces of a fireplace. Square, circular, or

octagonal, the central hearth was bordered by stone or tile and

sometimes had a backing of tile, brick or stone. Smoke rose

through a louver, a lantern-like structure in the roof with side

openings that were covered with sloping boards to exclude rain

and snow, and that could be closed by pulling strings, like

venetian blinds. There were also roof ventilators. A couvre-feu

(fire cover) made of tile or china was placed over the hearth at

night to reduce the fire hazard. When the hall was raised to the

second story, a fireplace in one wall took the place of the

central hearth, dangerous on an upper level, especially with a

timber floor. The hearth was moved to a location against a wall

with a funnel or hood to collect and control the smoke, and

finally, funnel and all, was incorporated into the wall. This

early type of fireplace was arched, and set into the wall at a

point where it was thickened by an external buttress, with the

smoke venting through the buttress. Toward the end of the 12th

century, the fireplace began to be protected by a projecting hood

of stone or plaster which controlled the smoke more effectively

and allowed for a shallower recess. Flues ascended vertically

through the walls to a chimney, cylindrical with an open top, or

with side vents and a conical cap.

If the later Middle Ages had made only slight

improvements in lighting over earlier centuries, a major

technical advance had come in heating: the fireplace, an

invention of deceptive simplicity. The fireplace provided heat

both directly and by radiation from the stones at the back, from

the hearth, and finally, from the opposite wall, which was given

extra thickness to absorb the heat and warm the room after the

fire had burned low. The ancestor of the fireplace was the

central open hearth, used in ground-level halls in Saxon times

and often into later centuries. Such a hearth may have heated one

of the two halls of Chepstow's 13th-century domestic range, where

there are no traces of a fireplace. Square, circular, or

octagonal, the central hearth was bordered by stone or tile and

sometimes had a backing of tile, brick or stone. Smoke rose

through a louver, a lantern-like structure in the roof with side

openings that were covered with sloping boards to exclude rain

and snow, and that could be closed by pulling strings, like

venetian blinds. There were also roof ventilators. A couvre-feu

(fire cover) made of tile or china was placed over the hearth at

night to reduce the fire hazard. When the hall was raised to the

second story, a fireplace in one wall took the place of the

central hearth, dangerous on an upper level, especially with a

timber floor. The hearth was moved to a location against a wall

with a funnel or hood to collect and control the smoke, and

finally, funnel and all, was incorporated into the wall. This

early type of fireplace was arched, and set into the wall at a

point where it was thickened by an external buttress, with the

smoke venting through the buttress. Toward the end of the 12th

century, the fireplace began to be protected by a projecting hood

of stone or plaster which controlled the smoke more effectively

and allowed for a shallower recess. Flues ascended vertically

through the walls to a chimney, cylindrical with an open top, or

with side vents and a conical cap.

In the 13th century the castle kitchen was still generally of timber, witha central hearth or several fireplaces wheremeat could be spitted or stewed in a cauldron. Utensils were washed in a scullery outside. Poultry and animals for slaughter were trussed and tethered nearby. Temporary extra kitchens were set up for feasts. In the bailey near the kitchen the castle garden was usually planted with fruit trees and vines at one end, and plots of herbs, and flowers - roses, lilies, heliotropes, violets, poppies, daffodils, iris, gladiola. There might also be a fishpond, stocked with trout and pike.

In the earliest castles the family slept at the extreme upper end of the hall, beyond the dais, from which the sleeping quarters were typically separated by only a curtain or screen. Fitz Osbern's hall at Chepstow, however, substituted for this temporary division a permanent wooden partition. Sometimes castles with ground-floor halls had their great chamber, where the lord and lady slept, in a separate wing at the dais end of the hall, over a storeroom, matched at the other end, over the buttery and pantry, by a chamber for the eldest son and his family, for guests, or for the castle steward. These second-floor chambers were sometimes equipped with "squints," peepholes concealed in wall decorations by which the owner or steward could keep an eye on what went on below.

The lord and lady's chamber, when situated on an

upper floor, was called the solar. By association, any private

chamber, whatever its location, came to be called a solar. Its

principal item of furniture was a great bed with a heavy wooden

frame and springs made of interlaced ropes or strips of leather,

overlaid with a feather mattress, sheets, quilts, fur coverlets,

and pillows. Such beds could be dismantled and taken along on the

frequent trips a great lord made to his castles and other manors.

The bed was curtained, with linen hangings that pulled back in

the daytime and closed at night to give privacy as well as

protection from drafts. Personal servants might sleep in the

lord's chamber on a pallet or trundle bed, or on a bench. Chests

for garments, a few "perches" or wooden pegs for

clothes, and a stool or two made up the remainder of the

furnishings. Sometimes a small anteroom called the wardrobe

adjoined the chamber - a storeroom where cloth, jewels, spices

and plates were stored in chests, and where dressmaking was done.

In the early Middle Ages, when few castles had large permanent

garrisons, not only servants but military and administrative

personnel slept in towers or in basements, or in the hall, or in

lean-to structures; knights performing castle guard slept near

their assigned posts. Later, when castles were manned by larger

garrisons, often mercenaries, separate barracks, mess halls, and

kitchens were built.

The lord and lady's chamber, when situated on an

upper floor, was called the solar. By association, any private

chamber, whatever its location, came to be called a solar. Its

principal item of furniture was a great bed with a heavy wooden

frame and springs made of interlaced ropes or strips of leather,

overlaid with a feather mattress, sheets, quilts, fur coverlets,

and pillows. Such beds could be dismantled and taken along on the

frequent trips a great lord made to his castles and other manors.

The bed was curtained, with linen hangings that pulled back in

the daytime and closed at night to give privacy as well as

protection from drafts. Personal servants might sleep in the

lord's chamber on a pallet or trundle bed, or on a bench. Chests

for garments, a few "perches" or wooden pegs for

clothes, and a stool or two made up the remainder of the

furnishings. Sometimes a small anteroom called the wardrobe

adjoined the chamber - a storeroom where cloth, jewels, spices

and plates were stored in chests, and where dressmaking was done.

In the early Middle Ages, when few castles had large permanent

garrisons, not only servants but military and administrative

personnel slept in towers or in basements, or in the hall, or in

lean-to structures; knights performing castle guard slept near

their assigned posts. Later, when castles were manned by larger

garrisons, often mercenaries, separate barracks, mess halls, and

kitchens were built.

Except for the screens and kitchen passages, the domestic quarters of medieval castles contained no internal corridors. Rooms opened into each other, or were joined by spiral staircases which required minimal space and could serve pairs of rooms on several floors. Covered external passageways called pentices joined a chamber to a chapel or to a wardrobe and might have windows, paneling, and even fireplaces.

Water for washing and drinking was often available at a central drawing point on each floor. Besides the well, inside or near the keep, there might be a cistern or reservoir on an upper level whose pipes carried water to the floors below. Hand washing was sometimes done at a laver or built-in basin in a recess in the hall entrance, with a projecting trough. Servants filled the tank above, and waste water was carried away by a lead pipe below, inflow and outflow controlled by valves with bronze or copper taps and spouts. Baths were taken in a wooden tub, protected by a tent or canopy and padded with cloth. In warm weather, the tub was often placed in the garden; in cold weather, in the chamber near the fire. When the lord travelled, the tub accompanied him, along with a bathman who prepared the baths.

The latrine, or "garderobe," not to be confused with the wardrobe, was situated as close to the bed chamber as possible (and was supplemented by the universally used chamber pot). Ideally, the garderobe was sited at the end of a short, right-angled passage in the thickness of the wall, often a buttress. When the chamber walls were not thick enough for this arrangement, a latrine was corbeled out from the wall over either a moat or river, as in the domestic range at Chepstow, or with a long shaft reaching nearly to the ground.

An indispensible feature of the castle of a great

lord was the chapel where the lord and his family heard morning

mass. In rectangular hall-keeps this was often in the

forebuilding, sometimes at basement level, sometimes on the

second floor. By the 13th century, the chapel was usually close

to the hall, convenient to the high table and bed chamber,

forming an L with the main building or sometimes projecting

opposite the chamber. A popular arrangement was to build the

chapel two stories high, with the nave divided horizontally; the

family sat in the upper part, reached from their chamber, while

the servants occupied the lower part.

An indispensible feature of the castle of a great

lord was the chapel where the lord and his family heard morning

mass. In rectangular hall-keeps this was often in the

forebuilding, sometimes at basement level, sometimes on the

second floor. By the 13th century, the chapel was usually close

to the hall, convenient to the high table and bed chamber,

forming an L with the main building or sometimes projecting

opposite the chamber. A popular arrangement was to build the

chapel two stories high, with the nave divided horizontally; the

family sat in the upper part, reached from their chamber, while

the servants occupied the lower part.